If

you’re lying awake in bed, and you look over at your sleeping partner

with their tongue hanging out, snoring, making odd farty noises, and

your heart starts beating faster and you think, “Of course! What a

brilliant idea for a horror story,” then congratulations, you have a

genuine muse on your hands.

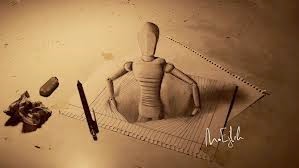

Sadly,

that’s not the case for everyone. Having someone who can inspire great

ideas and put thoughts in your head that lead to marvellous stories is

something we would all love, but the muse as an independent being who

feeds out creativity is a rare and unreliable creation.

So where can you go for a refill when your well runs dry?